Zeb

Vance once suggested to me a link to an anemometer design, see

reference below. Here is my somewhat

modified

version

of that circuit: The temperature sensing elements are the base-emitter

junctions of two probe transistors

Q1, Q2. The base-emitter junction voltage is typically 0.7 Volts with a

temperature

coefficient near -2 mV per deg C. The lower transistor Q2 has its

collector wired to its base. This one acts as a passive diode,

only there to sense ambient temperature. These transistors form the

left side of a

bridge, the right side is resistors R1, R2, and the trimmer R3.

Amplifier A1 senses the balance of the bridge. If the voltage over the

Q1 junction is too high, then A1 will drive the Q1 base up. More

current will pass through both transistors but Q2 is fully conducting

and does not change its temperature appreciably with change in current.

Having a high collector voltage, Q1 will be heated while Q2

remains essentially at ambient temperature. That heating lowers the Q1

base-emitter voltage until balance is restored. The heater and the

temperature detection are inherent

in the transistor itself. So A1 keeps Q1 a certain number of degrees

hotter than Q2. How many depends on the trimmer setting, with this

circuit typically around 5 degrees centigrade. Resistor R4 senses how

much current is flowing through Q1-Q2. The (small)

voltage developed over R4 by this current is amplified by A2 into the

output pin 7. A2 has an offset input but otherwise simply translates

the additional current needed to maintain the temperature difference

between the two B-E junctions. The more current, the more heat is being

removed from hot Q2. Actually A2 is not simple at all. If R9 and R10

are trimmers, you can go nuts trying to adjust them. The reason is that

“input offset” in the front. As the bias changes, the gain is affected.

Zeb

Vance once suggested to me a link to an anemometer design, see

reference below. Here is my somewhat

modified

version

of that circuit: The temperature sensing elements are the base-emitter

junctions of two probe transistors

Q1, Q2. The base-emitter junction voltage is typically 0.7 Volts with a

temperature

coefficient near -2 mV per deg C. The lower transistor Q2 has its

collector wired to its base. This one acts as a passive diode,

only there to sense ambient temperature. These transistors form the

left side of a

bridge, the right side is resistors R1, R2, and the trimmer R3.

Amplifier A1 senses the balance of the bridge. If the voltage over the

Q1 junction is too high, then A1 will drive the Q1 base up. More

current will pass through both transistors but Q2 is fully conducting

and does not change its temperature appreciably with change in current.

Having a high collector voltage, Q1 will be heated while Q2

remains essentially at ambient temperature. That heating lowers the Q1

base-emitter voltage until balance is restored. The heater and the

temperature detection are inherent

in the transistor itself. So A1 keeps Q1 a certain number of degrees

hotter than Q2. How many depends on the trimmer setting, with this

circuit typically around 5 degrees centigrade. Resistor R4 senses how

much current is flowing through Q1-Q2. The (small)

voltage developed over R4 by this current is amplified by A2 into the

output pin 7. A2 has an offset input but otherwise simply translates

the additional current needed to maintain the temperature difference

between the two B-E junctions. The more current, the more heat is being

removed from hot Q2. Actually A2 is not simple at all. If R9 and R10

are trimmers, you can go nuts trying to adjust them. The reason is that

“input offset” in the front. As the bias changes, the gain is affected. It

is hard to understand the talk about linearity in the original

article until you realize it is stated for a rather small range, up to

250 ft/min, 1.27 m/s. I find from my calibrations in the 1 to 10 m/s

range

that the device is close to logarithmic, as seen here in the

calibration for a probe with TO-18 case transistors. Its output

voltage increases about equally much for each doubling of the air

speed. And this is also the kind of behavior one would like to have,

this largely obviates need for a range switch.

It

is hard to understand the talk about linearity in the original

article until you realize it is stated for a rather small range, up to

250 ft/min, 1.27 m/s. I find from my calibrations in the 1 to 10 m/s

range

that the device is close to logarithmic, as seen here in the

calibration for a probe with TO-18 case transistors. Its output

voltage increases about equally much for each doubling of the air

speed. And this is also the kind of behavior one would like to have,

this largely obviates need for a range switch.

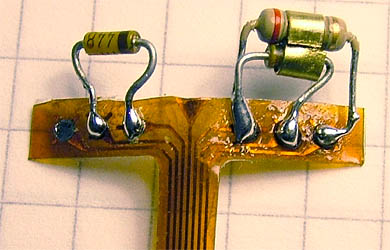

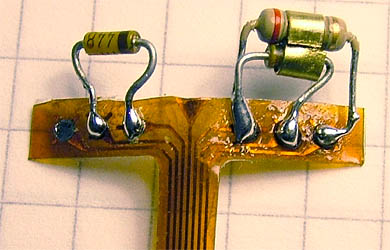

| This circuit remains with the principle of diode forward voltage temperature dependence, but now the hot diode is externally heated by a resistor. This diode was clamped to the heater with a tiny strip of brass sheet and also sealed to it with a drop of cyanoacrylate glue. The photo shows the probe tip cold and heated diodes. They are mounted on a flexible multiple conductor strip, retrieved from a head arm of a junked hard disk drive. The glass encapsulated 1N4448 diodes seem to have a fairly low thermal resistance, the data sheet says 0.24 K/mW including 10 mm leads. |  |

The

small voltage developed over R3 purports to govern the forward drop

difference, and hence the temperature difference between the diodes.

The

gain of the

balance sensing amplifier is by necessity moderated by the R5/R4

feedback network, together with a big slowing down capacitor C1.

There is a delay of heat transfer from the

heater to the heated diode. If the servo loop gain is too high, this

will make the circuit oscillate between fully on and off. The R6

heater resistor consumes more power than the bare amplifier can

deliver, so

an intermediate emitter follower transistor is added. The rather low

input voltage bias to the amplifier from the sensing diodes necessitate

D3

to increase the margin of amplifier negative supply.

The

small voltage developed over R3 purports to govern the forward drop

difference, and hence the temperature difference between the diodes.

The

gain of the

balance sensing amplifier is by necessity moderated by the R5/R4

feedback network, together with a big slowing down capacitor C1.

There is a delay of heat transfer from the

heater to the heated diode. If the servo loop gain is too high, this

will make the circuit oscillate between fully on and off. The R6

heater resistor consumes more power than the bare amplifier can

deliver, so

an intermediate emitter follower transistor is added. The rather low

input voltage bias to the amplifier from the sensing diodes necessitate

D3

to increase the margin of amplifier negative supply. This

circuit is simple, reliable, and sensitive. But one slight difficulty

may be to find a sufficiently low resistance thermistor such that it

can be driven enough hot at high speed, given the rather low supply

voltage. The alternative with R1=10k is for a very moderate temperature

rise, some 5K.

This

circuit is simple, reliable, and sensitive. But one slight difficulty

may be to find a sufficiently low resistance thermistor such that it

can be driven enough hot at high speed, given the rather low supply

voltage. The alternative with R1=10k is for a very moderate temperature

rise, some 5K. Also an externally heated version

was tried. The photo shows the probe with the hot NTC resistor lashed

with thin copper wire to the heater resistor. The original heater

resistor

leads are cut off and replaced by 0.24mm wire wrap leads to

reduce uncontrolled thermal leakage. The hot array is isolated from the

cold reference NTC resistor by a

lashing of sewing thread.

Also an externally heated version

was tried. The photo shows the probe with the hot NTC resistor lashed

with thin copper wire to the heater resistor. The original heater

resistor

leads are cut off and replaced by 0.24mm wire wrap leads to

reduce uncontrolled thermal leakage. The hot array is isolated from the

cold reference NTC resistor by a

lashing of sewing thread. This

circuit performs well, except for its inherent thermal delay between

heater and sensor. This necessitates

the slowing down feedback capacitor. Without it the circuit will

oscillate between on and off, with it the final reading is reached

after a prolonged delay, to the order of 30 seconds.

This

circuit performs well, except for its inherent thermal delay between

heater and sensor. This necessitates

the slowing down feedback capacitor. Without it the circuit will

oscillate between on and off, with it the final reading is reached

after a prolonged delay, to the order of 30 seconds. The hot wire anemometer is a

classical type and appears to

be the one

predominantly used for professional work. An orthodox such probe is

made

from Wollaston wire, a thin silver wire with a platinum core (priced

like US$ 500 for 8 inches of it). After soldering it to its posts under

a microscope you etch away the silver to leave a sub micrometer

diameter platinum wire. An exercise well beyond most amateurs.

The hot wire anemometer is a

classical type and appears to

be the one

predominantly used for professional work. An orthodox such probe is

made

from Wollaston wire, a thin silver wire with a platinum core (priced

like US$ 500 for 8 inches of it). After soldering it to its posts under

a microscope you etch away the silver to leave a sub micrometer

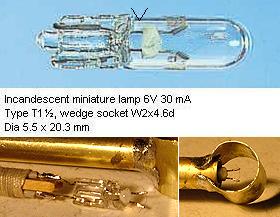

diameter platinum wire. An exercise well beyond most amateurs.  It must

be noted that without its bulb and inert atmosphere the

filament can not withstand anywhere near the original lamp

specification before being burned out. Be aware the lamp

cold resistance is 10-20 times lower than what is given by nominal

voltage and power. This particular lamp happens to

have

20 ohms cold resistance. For tungsten the resistive temp coefficient is

0.0045 /K such that the bridge balance value of 22 ohms is reached at

about 22 degrees centigrade temperature elevation. This is a very

moderate rise, such that correction will be necessary if ambient

temperature deviates appreciably from normal. Tweaking the fixed

resistor values in the bridge allows for some other temperature level.

On one hand R2 should be large enough to ensure the filament is never

burnt out. On the other hand R2 and supply voltage limit heating

current

such that there is a definite maximum measurable speed.

It must

be noted that without its bulb and inert atmosphere the

filament can not withstand anywhere near the original lamp

specification before being burned out. Be aware the lamp

cold resistance is 10-20 times lower than what is given by nominal

voltage and power. This particular lamp happens to

have

20 ohms cold resistance. For tungsten the resistive temp coefficient is

0.0045 /K such that the bridge balance value of 22 ohms is reached at

about 22 degrees centigrade temperature elevation. This is a very

moderate rise, such that correction will be necessary if ambient

temperature deviates appreciably from normal. Tweaking the fixed

resistor values in the bridge allows for some other temperature level.

On one hand R2 should be large enough to ensure the filament is never

burnt out. On the other hand R2 and supply voltage limit heating

current

such that there is a definite maximum measurable speed. To

get an air stream of known speed I used a vacuum cleaner, fed from a

variable transformer. That way the fan speed could be set arbitrarily

over some range. The cleaner hose was connected to a Venturi tube to

measure flow rate and the device ended with a nozzle where the probe

under test was placed centrally. To extend the measurement range I

could alternate between 22, 46

and 86 mm diameter nozzles. Knowing its diameter and

assuming a uniform air speed over its intake area A (m2) it

is

elementary to convert from flow Q (m3/s) into speed V (m/s):

V = Q/A. After running for a while the fan will heat the air passing

it. To avoid spurious effects from that, air was sucked from the

room rather than blown out from the nozzle.

To

get an air stream of known speed I used a vacuum cleaner, fed from a

variable transformer. That way the fan speed could be set arbitrarily

over some range. The cleaner hose was connected to a Venturi tube to

measure flow rate and the device ended with a nozzle where the probe

under test was placed centrally. To extend the measurement range I

could alternate between 22, 46

and 86 mm diameter nozzles. Knowing its diameter and

assuming a uniform air speed over its intake area A (m2) it

is

elementary to convert from flow Q (m3/s) into speed V (m/s):

V = Q/A. After running for a while the fan will heat the air passing

it. To avoid spurious effects from that, air was sucked from the

room rather than blown out from the nozzle. The flow meter

Venturi tube has two probe holes to measure the pressure drop from

input to constriction. By virtue of the Bernoulli law this drop is

proportional to the

square of the flow rate and was taken with a water U manometer, later

with a differential pressure transducer. The tube was calibrated by

measuring the time elapsed to fill a plastic bag of known volume. The

Venturi expands gradually after the constriction such that pressure is

partially regained. This has nothing to do with the flow measurement as

such, but it reduces the throttling effect of the meter.

The flow meter

Venturi tube has two probe holes to measure the pressure drop from

input to constriction. By virtue of the Bernoulli law this drop is

proportional to the

square of the flow rate and was taken with a water U manometer, later

with a differential pressure transducer. The tube was calibrated by

measuring the time elapsed to fill a plastic bag of known volume. The

Venturi expands gradually after the constriction such that pressure is

partially regained. This has nothing to do with the flow measurement as

such, but it reduces the throttling effect of the meter.| One would like to

know the temperature of the probe element. For the thermistor and hot

wire this is simple since the bridge

balance criterion (same resistance ratio both sides) tells about their

hot

electrical resistance. For those the temperature can then be computed

from their known cold resistance and the temperature coefficient. For a direct measurement I used a small oil filled container, carried on a digital thermometer probe. First the anemometer circuit was left to stabilize in still air and its output voltage was recorded. The container was heated with a soldering iron and was then left to cool down slowly while its temperature was tracked by the thermometer. At intervals the probe hot element was dipped into the oil. At the point where the anemometer output then stayed at its earlier recorded value, the oil temperature equals that of the probe tip. The small paper wing in the photo was to shield the cold reference sensor from hot air rising from the oil bath. |

|

At left

is a generator that injects power P

(Watts) into

the circuit. C is

the thermal capacity of the device (e.g. transistor) measured in Joule

(Watt*seconds) per

degree (Kelvin or Centigrade), and the internal temperature of it

(junction temp) is To.

All

temperatures are relative to ambience = 'ground'.

At left

is a generator that injects power P

(Watts) into

the circuit. C is

the thermal capacity of the device (e.g. transistor) measured in Joule

(Watt*seconds) per

degree (Kelvin or Centigrade), and the internal temperature of it

(junction temp) is To.

All

temperatures are relative to ambience = 'ground'.

External

heating eliminates the problem that heating power injection may

interfere with the temperature sensing. Here is what I figure is a

relevant though simplified thermal analogy

for an externally

heated probe. The sensor is enclosed in a separate

body, thermally connected to the heater by Ro which includes its

internal drop. Now there is a

distinction between the thermal capacity

Ch of the

heater and that of the sensor, Cs.

The Ro-Cs circuit makes a

low pass

filter that slows down operation and raises a stability problem to be

handled by the electrical feedback circuit. For instance, when Cs is being heated and

reaches the target temperature Ts,

then the circuit turns off power. Despite that, Cs will be even more

heated from the energy already stored in Ch.

External

heating eliminates the problem that heating power injection may

interfere with the temperature sensing. Here is what I figure is a

relevant though simplified thermal analogy

for an externally

heated probe. The sensor is enclosed in a separate

body, thermally connected to the heater by Ro which includes its

internal drop. Now there is a

distinction between the thermal capacity

Ch of the

heater and that of the sensor, Cs.

The Ro-Cs circuit makes a

low pass

filter that slows down operation and raises a stability problem to be

handled by the electrical feedback circuit. For instance, when Cs is being heated and

reaches the target temperature Ts,

then the circuit turns off power. Despite that, Cs will be even more

heated from the energy already stored in Ch. | Section |

1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Quantity |

Symbol |

Dimension |

TO18

Cu leads |

TO18

Fe leads |

SOT23

Cu leads |

SOT23

Fe leads |

Ext Diode | NTC bridge | Ext NTC | Lamp

24V |

Lamp

6V 30mA |

| Int.

res. |

Ro | K/mW |

0,24 | 0,24 | 0,22 | 0,21 | 0,03 | 0,10 | 0,02 | 0,12 | 0,35 |

| Loss

res. |

Rl | K/mW | 0,09 | 0,13 | 0,07 | 0,55 | 0,12 | 0,24 | 0,19 | 2,18 | 6,90 |

| Cool

coeff. |

kRv | K(m/s)/mW |

0,15 | 0,09 | 0,47 | 0,30 | 0,11 | 0,38 | 0,25 | 1,06 | 7,43 |

| Temp.

rise |

dT | K |

30 | 39 | 29 | 32 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 20 | 22 |

| Error

|

E | % |

0,4 | 0,6 | 0,4 | 2,2 | 2,7 | 4,4 | 9,6 | 13,0 | 7,4 |

| Quality |

Rl/Ro | - |

0,4 | 0,5 | 0,3 | 2,7 | 4,6 | 2,3 | 11,4 | 19,0 | 19,6 |

| Mid

speed |

Vmed | m/s |

2,4 | 1,1 | 8,9 | 2,0 | 5,1 | 5,2 | 16 | 9,7 | 22 |

| Time const |

t |

s |

30 |

40 |

4 |

3 |

15 |

4 |

10 |

- |

- |

|

This figure shows what indicator

meter scales would look like for the

various alternatives. They are derived from the actually measured

voltages and are expanded such that the range is from 0 to 20m/s. The

figures at left is the U voltage for the scale left end (0) in percent

of that for full scale (20). With the lower quality probes this offset

is rather high. These scales differ from the earlier theoretical examples since heating power and U are not directly proportional in the bottom five cases. I find no obvious explanation to why the scale for the NTC bridge comes so very close to an ideal logarithmic. |

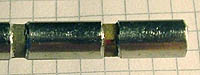

| Photo |

Sect/Type |

Comment |

|

1.1 TO18 |

Rugged form with transistors potted inside an aluminum tube using Araldit two component epoxi. The increased masses and thermal resistances make the settling time several minutes. Sensitivity was reduced to about half, and it turned out bad in reproducing calibration. Looks nice, but is completely useless. |

|

1.5 Lamp 12V 5W |

Halogen lamp. Cold resistance

less than 1 ohm requires additional power drive. |